Final Work

I-95 in Philiadelphia

Introduction

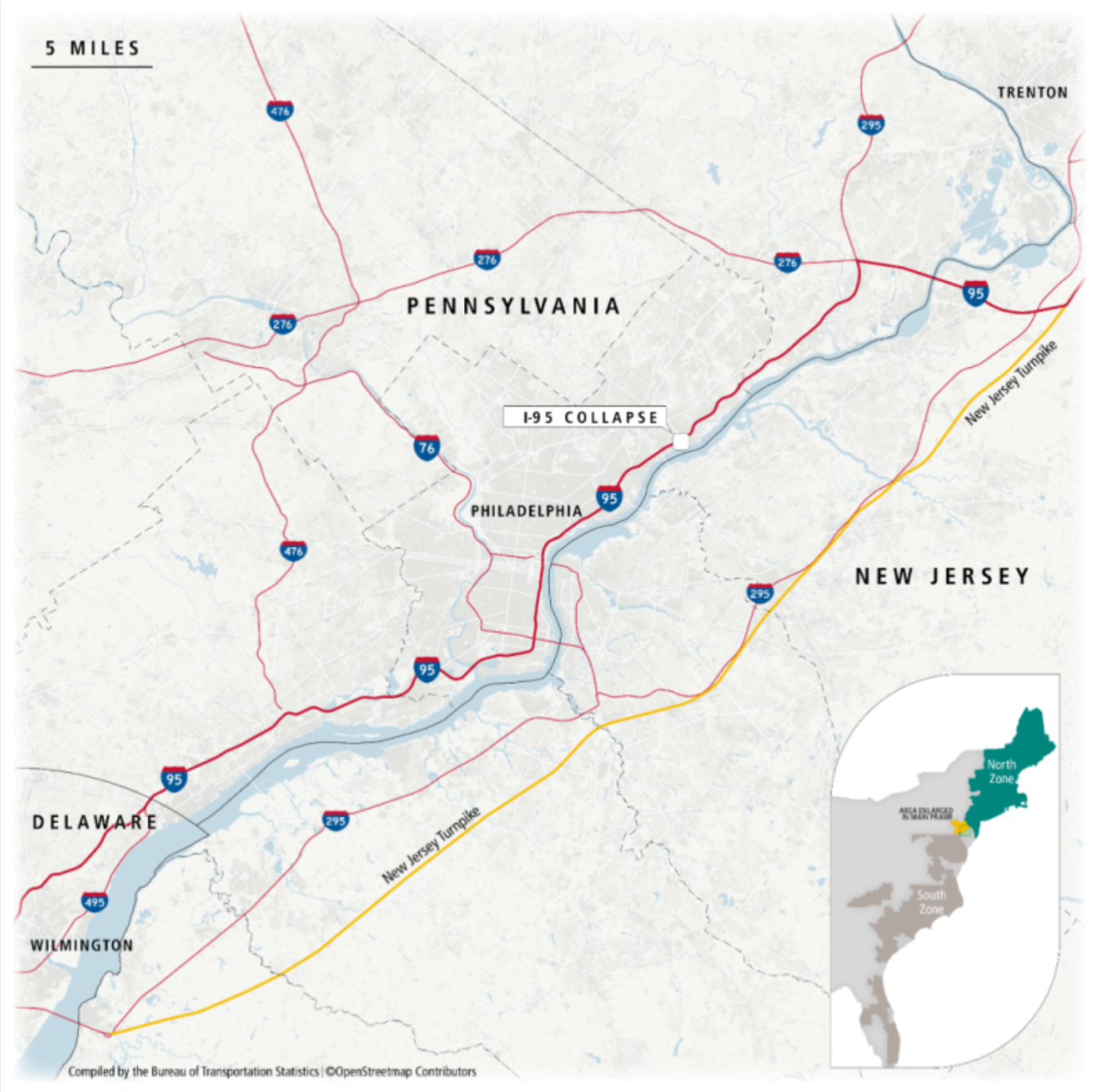

Interstate 95 is a defining feature of modern Philadelphia: a vital regional artery that simultaneously fractured the city’s urban landscape. Its history reflects the core trade-offs of mid-century highway policy, in which national goals of mobility and economic growth were pursued at the expense of local communities. To stay within budget, planners routed I-95 along the Delaware River, choosing the cheapest land available and, in the process, severing long-established neighborhoods from one of the city’s most important natural and cultural resources. This achievement of infrastructure was therefore built through disruption, as it displaced residents, erased historic blocks, and transformed the waterfront into a barrier rather than a shared public space. Yet the legacy of I-95 is not solely one of division. After decades of living with the highway’s effects, Philadelphia has begun actively working to repair the damage and reconnect its people to the river. Current initiatives, such as the construction of land bridges and capped sections near Penn’s Landing, represent a collective effort to restore access, rebuild community cohesion, and reshape the relationship between the city and its waterfront. Together, these developments illustrate both the enduring consequences of past planning decisions and the potential for contemporary design to heal the urban fabric.

Conception

Long before the I-95 highway would be built, in 1937, the highway's predecessor, the Delaware Skyway, would make its rounds across the Philadelphia City Planning Commission. It did not survive the journey, but its ideas should be explored with President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956.

After World War II, President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s wartime encounter with Germany’s autobahn system profoundly moved him. According to PlanPhilly, “Dwight Eisenhower had encountered Germany’s autobahn system during the war in Europe and, as president, championed two major justifications for the American interstates: Speeding everyday commerce and travel, and allowing rapid troop movements in the event of invasion.” (PlanPhilly 2007) The system was thus simultaneously an economic and strategic undertaking, one that framed highways as instruments of national modernization.

It is important to note that the President's role in the passing Federal-Aid Highway Act is greatly exaggerated. While he did advocate for highways, this was not the bill he supported. He had non-government professionals write the bill, but it was downvoted in 1955. What we know now as the Federal-Aid Highway Act was written by congress Democrats.

Impact

The routing of Interstate 95 through Philadelphia was shaped less by urban design considerations and more by cost containment and political expediency. As planners sought to minimize expenses associated with right-of-way acquisition, they selected the cheapest land available such as industrial parcels, working-class neighborhoods, and waterfront tracts along the Delaware River. While this approach reduced the project’s financial burden, it produced severe and lasting consequences for the communities in its path. Entire blocks were demolished, residents were displaced, and long-standing social networks were fractured. In Southwark alone, about 2,000 homes were destroyed, along with businesses, churches, and blocks of historic housing (Murrell 2025) . In neighborhoods such as Fishtown, Kensington, Pennsport, and Society Hill, the construction of I-95 introduced an elevated or sunken physical barrier that fundamentally altered patterns of movement and access. PlanPhilly notes that “Citizen opposition in Society Hill was more vocal. An architect named Frank Weise led resistance to the road after viewing a scale model of the project.” (PlanPhilly 2007). I personally think that it is not a coincidence that the only notable opposition came from the richest neighborhoods. I believe that it is not that they were more vocal, but rather they were the only neighborhood people cared to listen to, as it is the richest neighborhood affected by the highway.

Historically, the Delaware River served as Philadelphia’s economic and cultural lifeline. The highway’s construction disrupted this relationship, turning the waterfront into a peripheral and largely inaccessible zone dominated by traffic, noise, and parking lots. In an effort to minimise the cost, the city planning commission “severed the city from one of its most important natural resources” (PlanPhilly 2007) The elevated viaducts and expansive interchanges not only overshadowed adjacent streets but also contributed to environmental degradation through air pollution, runoff, and the intensification of heat-retaining surfaces.

The economic impacts were similarly multifaceted. While I-95 facilitated the movement of goods and commuters across the region, its presence depressed local property values in certain areas and accelerated patterns of suburbanization that drew investment away from the urban core. Commercial corridors near the highway saw decreased foot traffic and diminished vitality, while the surrounding neighborhoods faced decades of underinvestment. These outcomes mirrored national trends in mid-century highway construction, in which infrastructure intended to support national mobility often undermined the economic and social foundations of the communities it passed through.

I-95 And Its Future

Today, Interstate 95 remains both an indispensable transportation corridor and a persistent point of tension within Philadelphia’s urban fabric. Much of the highway, built in the mid-twentieth century with a fifty-year design life, is now undergoing an extensive, multi-decade reconstruction effort. PennDOT’s “I-95 Revive” program represents the systematic rebuilding of aging viaducts, ramps, and expanding with new lanes from South Philadelphia through the Northeast.

In recent years, the most visible part of this effort has been at Penn’s Landing, where the city and PennDOT are capping a section of I-95 with an 11.5-acre park designed to reconnect Center City to the Delaware River. This project has become a symbol of Philadelphia’s attempts to heal the physical and psychological divide that the highway created. By burying the roadway beneath green space and public amenities, planners aim to restore walkability, stimulate waterfront development, and reestablish the river as a civic asset rather than a distant boundary. It is important to note that this is only happening in one of the richer neighborhoods affected by the highways.

The story of I-95 in the present is far from universally optimistic. Reconstruction and expansion plans in South Philadelphia have sparked intense controversy. A 2025 Philadelphia Magazine investigation reported that PennDOT’s proposed widening of I-95 would add lanes and construct new ramps through residential neighborhoods, even crossing directly over community spaces such as the Southeast Youth Athletic Association fields. Residents of Whitman, Pennsport, Queen Village, and surrounding areas have criticized the agency for limited outreach, confusing surveys, and for advancing an option that many believe will increase noise, pollution, and neighborhood fragmentation. (Murrell 2025) The same article recounts how the original construction demolished thousands of homes, including roughly 2,000 in Southwark, and many fear that widening the highway will repeat patterns of harm rather than repair them.

The story of I-95 in the present is far from universally optimistic. Reconstruction and expansion plans in South Philadelphia have sparked intense controversy. A 2025 Philadelphia Magazine investigation reported that PennDOT’s proposed widening of I-95 would add lanes and construct new ramps through residential neighborhoods, even crossing directly over community spaces such as the Southeast Youth Athletic Association fields. Residents of Whitman, Pennsport, Queen Village, and surrounding areas have criticized the agency for limited outreach, confusing surveys, and for advancing an option that many believe will increase noise, pollution, and neighborhood fragmentation. (Murrell 2025) The same article recounts how the original construction demolished thousands of homes, including roughly 2,000 in Southwark, and many fear that widening the highway will repeat patterns of harm rather than repair them.

Residents in Philadelphia have the power to become more than silent observers. It is critical we use all the tools in front of us in order to protect our historic neighborhoods. Through neighborhood coalitions, participation in PennDOT’s mandated public engagement process, mobilization during environmental impact reviews, and direct advocacy to elected officials, residents possess meaningful tools to contest the widening of I-95 and promote alternatives that prioritize public health, environmental justice, and community cohesion. Public comment, media engagement, and partnerships with urban planning and environmental researchers further amplify these efforts, ensuring that community voices remain part of the fight that shapes final decisions.